The Road Trip

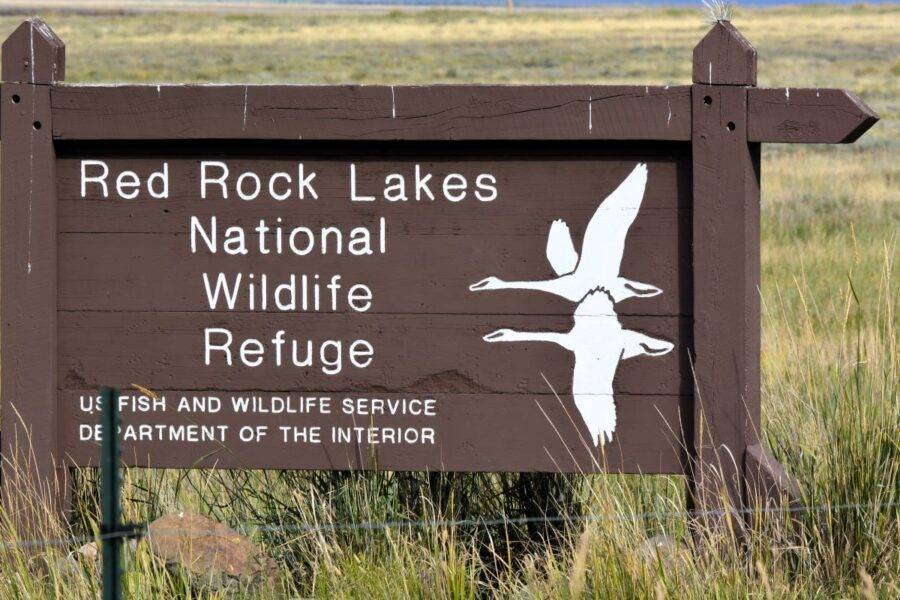

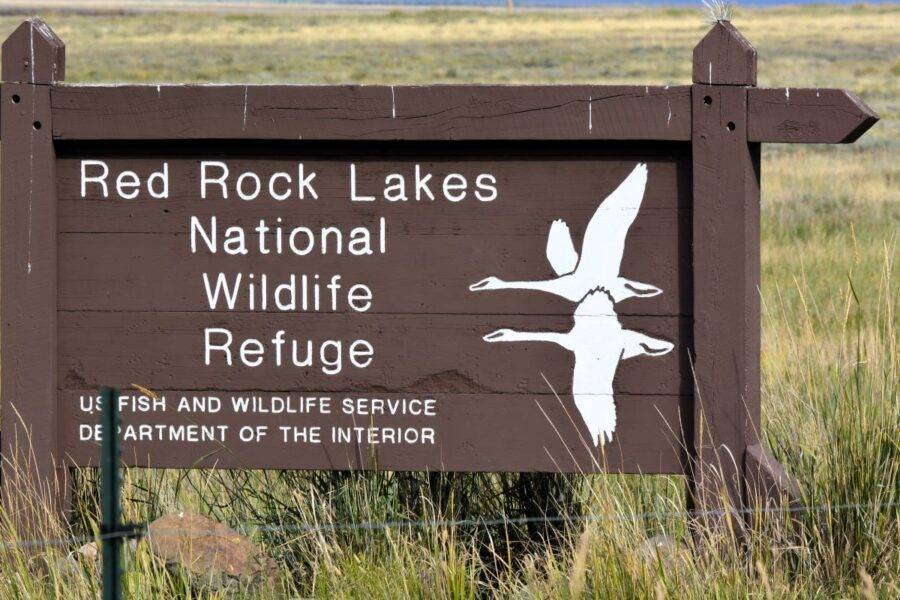

Early in 2022, while reading a book titled America’s National Wildlife Refuges, I became enthralled with a refuge in southwestern Montana called Red Rock Lakes. According to the book’s author, the refuge was established in 1935 to help rescue the trumpeter swan—America’s largest waterfowl species—from extinction. “You should see this,” I said to Kathy. “I’ve never seen a trumpeter swan, a moose, or a grizzly bear in the wild. This refuge has them all!”